During our 6 month stint, our main task at the Education Offices is to conduct an organisational assessment, so that the Director and her colleagues can identify the priorities for improvement. During this week, we have been working closely with the Deputy Director of education, in advance of a meeting to be held next week with a group of education officers. The outcomes of the assessment should help the organisation to seek and obtain support and finance to be used on relevant priorities.

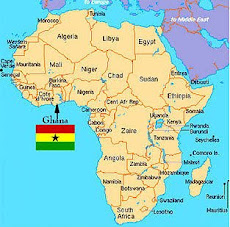

Our recent travels around Ghana have enabled us to see how parts of the country differ. It is really interesting to see the wide range of house styles and living conditions throughout the country. In the major towns and cities there are some very large, expensive dwellings made of brick and concrete, with beautiful gardens. However, this is not typical. In the villages and small towns, it is much more usual to see houses constructed of locally available materials. For example, in the south and central areas of the country, houses are typically constructed of a wooden frame that is then covered in mud or filled with mud bricks. The stems of local cereal crops and grasses are then used to construct a thatched roof. Many of these houses are oblong in shape.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Heading further north, the houses have a similar structure, but they are typically round in shape, and groups of 5 or 6 houses are grouped together within the village. Most of these villages have no electricity supply, and the women and children often have to walk long distances each day to fetch water.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Some villages have their own specific traditions in house building. For example, in the village of Paga, the walls of the houses are made of a mixture of mud and cow dung. For centuries, the women have then painted pictures on the outside of the houses. The house below is over 2 hundred years old and is not currently inhabited.

.jpg)

The Paga house in the picture below is the same age and is still used for women to give birth. The woman will remain in the house for about a week after the birth, during which time she is fed and entertained with drumming and dancing by members of the village.

.jpg)

In Paga, the walls of houses are still made with mud and cow dung, but they now tend to have roofs made of corrugated iron. The villagers told us that they prefer the older style thatched houses, because they are much cooler.

In the most northern, hotter regions, the people generally live in compounds that are made totally of mud, with flat mud roofs. The roofs are used for drying grain and fruit, and for erecting shrines to the ancestors and lesser gods. They are also used as somewhere to sleep, when the weather is particularly hot. These compounds vary in size and they house between 12 and 70 people from the same extended family. All are made of mud in one of 2 types of construction. Sometimes, round balls of mud are kneaded together to make the walls. This takes rather a long time, because only a few layers can be built at a time. These layers have to be left to dry out, before the next few layers can be added. Alternatively, mud bricks, made in moulds, are used. These are more expensive to produce, but compounds can be constructed more quickly, as there is no need to leave the bricks to dry out. Therefore labour costs are lower. The compounds are constructed by “master builders”, working with volunteers from the village. It is expected that master builders will be paid, usually with tobacco, alcohol, kola nuts etc. It is expected that the volunteers will be fed. Once constructed, the walls are covered with a plaster that is made of about 3 layers of fine silt/gravel and cow dung.

.jpg)

In the northern village of Sirigu, the people also live in compounds, and there is a centuries old tradition of painting the compounds. Many of the designs have cultural and historical significance. Once the walls are constructed, women carry out the painting, using the colours of red, black and white, made from local rocks. Specialist painters are employed, supported by volunteers from the village community. In more recent times, modern designs have become incorporated into the painting, including Christian symbolism e.g. angels and crosses. When the painting is complete, it is covered with a protective gloss, which also makes the colour brighter and shiny. This layer is made of various leaves and tree bark that is boiled in water. All painting is done with feathers. Villagers report that the painting is done in order to protect the walls, and as a way of enabling the women of the village to express themselves.

.jpg)

In Sirigu, each compound has a fairly consistent structure. There is a reception area outside the compound, usually a shelter made of wood and straw. Logs are also placed in this area to act as seating. On entry to the compound, the first place to encounter is the animal courtyard. Goats and cows are kept here at night, and they act as a warning if anyone tries to enter the compound. Houses for chickens are built into the mud of the walls. Grain is also stored in this area in silos of a mud construction. Each silo has a removable thatched roof. Grain storage is vital to families, because virtually no crops can be grown and harvested in the dry season. It is necessary to step over a low mud wall into the next courtyard. Some compounds will have 1 courtyard; others will have 6 or 7. All the living accommodation is off the courtyard(s). The best room goes to the oldest man in the compound, followed by the oldest woman. Polygamy is common, and each wife is entitled to her own room for herself and her children. When a woman marries, she moves to her husband’s compound. Most living/cooking etc. is done outdoors in the courtyards. We visited the compound of the Sirigu Chief, who has 6 wives. Custom therefore dictates that no man in the village can have more than 5 wives.

.jpg)

.jpg)

In Wa, as in other towns, the majority of houses are made of mud bricks, with metal roofs. The development of the infrastructure has not kept pace with the growth of the town, and open sewers run amongst the houses. This means that people live amongst goats, chickens, rubbish and raw sewage. It is amazing to us how the local people keep themselves, their clothing and their cooking utensils so clean. The morning routine in every household involves sweeping the rooms and the courtyard, a chore that continues at school for young people.

.jpg)

The house below is most untypical of Wa, but a few of this type do exist in the major towns.

.jpg)

On the lighter side, living in Ghana requires us to be adaptable and inventive. When the only internet signal available is obtained by sitting at a specific angle in the garden, facing the wall, then that’s what you do:

.jpg)

When the gas cylinder runs out and there is no electricity and you are in the middle of cooking, then you get out the charcoal and a neighbour’s “coal pot” and cook outside, sitting on the floor like a true Ghanaian.

.jpg)

Hope all UK readers are coming safely and comfortably out of that cold spell that we missed!!